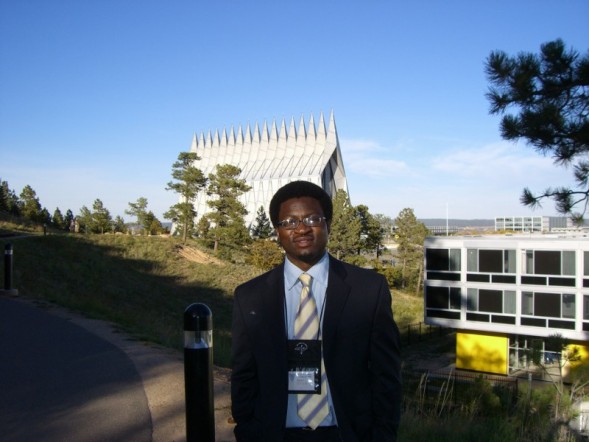

In 1992, I arrived in the United States for the first time as one of just 10 foreign cadets admitted to the 4-year program at the United States Air Force Academy, where I majored in Aeronautical Engineering, minored in French, completed solo and aerobatic flight training in the T-3, flew gliders, earned my free-fall parachutist jump wings, coached intramural boxing, and published the novel "Boy Soldiers of the Savannah," becoming the first cadet to write and publish a novel while at the Academy.

I look back to a very busy four years at the Academy, where I also averaged 24 credits per semester and made the National Dean's List. I was also selected a member of both the National Honor Society for Aeronautical and Aerospace Engineers and the Engineering Honor Society.

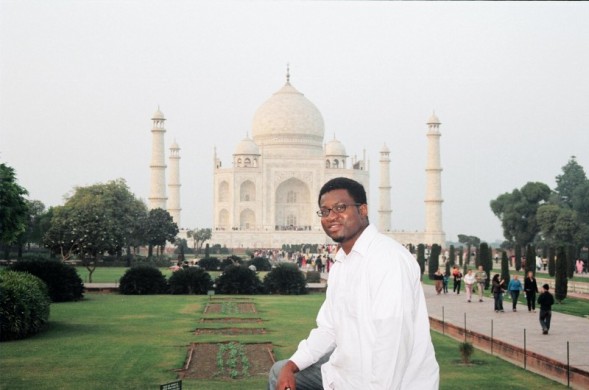

After graduating from the United States Air Force Academy, I sought and was granted political asylum in the United States due to the serious risk I faced of persecution in my home country for my criticism, in various media outlets, of the military dictatorship of the late General Sani Abacha.

With a scholarship, I proceeded to Cornell Law School, where I was selected a member of the Cornell Law Review. My first law school summer internship was at the Center for Capital Litigation in Columbia, South Carolina, where I interviewed death row inmates, their relatives and jurors, gathering evidence for habeas corpus appeals. My second summer internship was at the top tier Wall Street law firm of Cleary, Gottlieb, Steen & Hamilton working on corporate securities transactions.

I first ventured into business when I founded MovieShares.com at the end of my first year in law school. This was the dawn of the dot-com era and I had been inspired by a microbrewery called Spring Street which had successfully completed the first online public offering. I felt if an online public offering could be successful for a microbrewery, it could be possible for my film script "First Squad," which was based on the novel I had written while at the Academy. I also felt that if my film could be financed online, others could as well. This was how the idea MovieShares was born -- and I hoped to build a company that would hold court at the intersection of Wall Street, Hollywood and the Internet. A couple months later, I brought my law school classmate and fellow movie enthusiast Kamran Pasha on board. Kamran's task was to focus on finding venture capital and other financing, while I was to continue to focus on Internet operations, strategy and regulatory issues.

I drafted our first no-action letter to the Securities and Exchange Commission to address any broker-dealer registration concerns the SEC may have had. I felt that to address SEC broker-dealer concerns, the company would have to finance films by issuing various classes of stock tied directly to the performance of the underlying films and that the company would have to play a major and direct role in the production of those films. I felt that instead of MovieShares acting as just a middleman between investors and filmmakers, MovieShares would have to produce the films itself, albeit in conjunction with the filmmakers. This would address securities law and branding concerns. Bad movies would dilute the MovieShares brand, so we had to ensure that the movies we raised money for had a high probability of being not just artistically successful, but financially lucrative for our investors as well.

We raised six figures in financing at a valuation of several million dollars. With over 70 percent in equity, I was worth quite a bit on paper, albeit with little in hard dollars in the bank to show for it.

After law school, I needed a "real" job, and gladly accepted an offer for the position of associate at Cleary Gottlieb, the Wall Street law firm. They started me at about $165,000 (bonuses included). For a 27-year-old wet-behind-the-ears recent immigrant, that was a pretty sum -- oh, the land of opportunity. But my mind was not at the law firm. I had other dreams. And after some months had passed, I sent out an early resignation letter to the law firm, informing them I was planning to leave in a month. I was going to join Kamran Pasha full-time to ensure the success of MovieShares. At this time, Kamran had left Cornell Law School and was now completing the second-half of his joint JD/MBA at the Tuck School of Business at Dartmouth. We decided that given his access to contacts in the B-school at Tuck, he was in the best position to serve as CEO, and that he was to work towards getting some of his Tuck School classmates on board -- which he did successfully.

Then just as I was about to leave the firm to join Kamran at MovieShares, the U.S. stock market took a nosedive. Some thought it was temporary, but I knew it was the end of a market era. That was my first experience with the bursting of a market bubble, but I knew what I heard was definitely a pop.

This led me to my first lesson in business. You may have heard of the late Iowa State University professor Everret Rogers' 1962 book, "Diffusion of Innovations," where he describes five categories of technology adopters. He called them the innovators, the early adopters, the early majority, the late majority and the laggards. I use these categories to describe businesses entering into a market. Lesson learned: When you spot the first member of the late majority making an entrance, it's time to swim upstream. If the late majority is buying, sell. If they need the technology, supply. If they're doing the same thing you're doing, innovate. It's a delicate balance. If you're way ahead of your time, no body gets it. Swim upstream at the right time. This applies to consumers as well. When Nana is telling you about this "sweet" stock she heard about at a church basement bingo party, run ... and take her with you.

Monday, November 17, 2008

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)